Research Highlight from Asia- New Jurassic Fossil Sheds Light on the Origins of Parasitic Thorny-Headed Worms

A remarkable 165-million-year-old fossil discovered in China has unveiled critical insights into the evolutionary history of acanthocephalans, a group of parasitic worms known as “thorny-headed worms.” Published in Nature, the study describes Juracanthocephalus daohugouensis, the first body fossil of an acanthocephalan from the Middle Jurassic, bridging a long-standing gap in understanding how these parasites evolved from free-living ancestors.

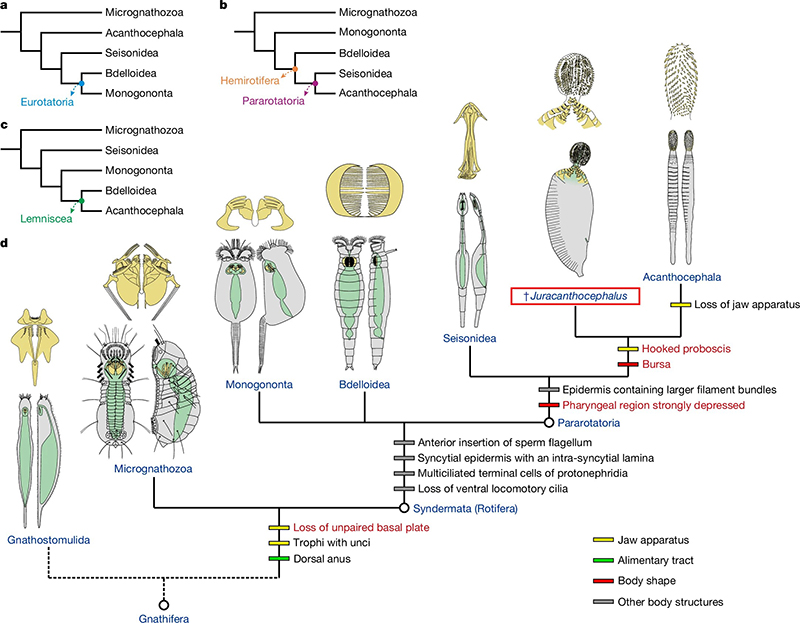

Acanthocephalans, characterized by their spiny, hook-lined proboscis used to latch onto host tissues, are notorious parasites inhabiting vertebrates and invertebrates. While molecular studies have linked them to rotifers (microscopic aquatic animals), their early evolution remained murky due to a near-absence of fossils. Prior to this discovery, the only known acanthocephalan fossils were eggs from the Late Cretaceous, offering limited clues about their body plan or ecological transition to parasitism.

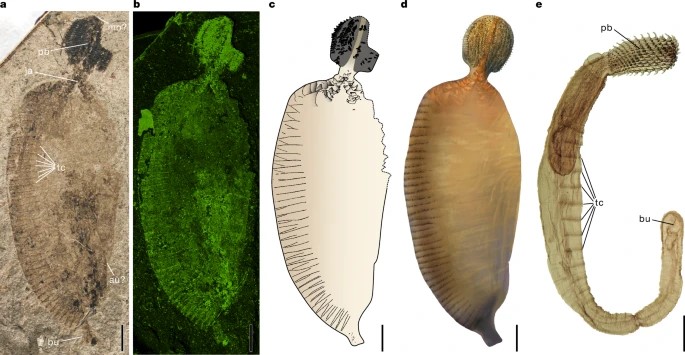

The newly identified fossil, unearthed from the Daohugou biota in Inner Mongolia, preserves exceptional soft-tissue details. Measuring 23.4 mm in length, Juracanthocephalus exhibits a mix of ancestral and specialized traits. Its semi-oval proboscis, armed with spiral rows of hooks, aligns with modern acanthocephalans. However, it also retains a jaw apparatus and possible digestive system—features lost in extant species, which absorb nutrients directly through their skin. These traits position Juracanthocephalus as a transitional form, linking jawed rotifers to jawless, fully parasitic acanthocephalans.

“This fossil captures a pivotal stage in the evolution of parasitism,” said Dr. Bo Wang, senior author of the study. “It shows that key parasitic structures, like the hooked proboscis, evolved before the loss of the digestive system, suggesting a stepwise adaptation to an endoparasitic lifestyle.”

Phylogenetic analyses place Juracanthocephalus within Gnathifera, a group including rotifers and jawed worms, and as a stem-group acanthocephalan. Its anatomy supports molecular hypotheses that acanthocephalans originated within rotifers, specifically as sister to Seisonidea—a group of epizoic (surface-dwelling) rotifers. This challenges earlier theories proposing a Cambrian marine origin, instead hinting at a terrestrial or freshwater ancestry.

The fossil’s large size suggests it likely parasitized vertebrates, such as Jurassic salamanders or early mammals found in the Daohugou deposits. Preservation in volcanic ash indicates the worm may have been expelled from a host or killed during a volcanic event, enabling its rare fossilization.

This discovery underscores the importance of transitional fossils in resolving evolutionary conflicts. “Molecular data alone often leave gaps,” explained co-author Dr. Luke Parry. “Fossils like Juracanthocephalus provide tangible evidence of how radical anatomical changes occurred over time.”

The study also highlights the ecological diversity of ancient acanthocephalans and opens new avenues for exploring the origins of parasitism in other worm lineages. Researchers plan to investigate additional Jurassic fossils to refine the evolutionary timeline and uncover how these parasites colonized diverse hosts across millennia.

REFERENCE

Luo, C., Parry, L.A., Boudinot, B.E. et al. A Jurassic acanthocephalan illuminates the origin of thorny-headed worms. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08830-5

Attachment Download: